EARLY COLONIZATION

Our histories are not simply a past occurrence, with a linear cause and effect, but a tangled lattice that spans time in all directions, including our realities today. Indigenous societies didn't passively collapse but adapted, resisted, and reformed. These processes were complex and varied widely depending on local contexts. To understand how the violence and militarization of colonization has materialized into our ancestors,’ and therefore our realities, we must follow the threads of this lattice - through all its kinks and folds.

Colonization dismantled existing social and ecological systems. Indigenous knowledge networks, trade routes, and governance structures were either co-opted or destroyed. Colonization was destructive yet new assemblages emerged. Conflicts and alliances between native tribes and settlers created an evolving landscape that was highly nonlinear. For instance, European goods, firearms, and horses integrated into native cultures, fundamentally altering social dynamics and war machines. The Comanche, for example, became dominant through their mastery of horseback combat. While the Apache, became masterful riflemen. Yet these new assemblages were still under the pressure of invading and destructive forces.

The displacement of Apaches and Comanches from the north-northwestern Texas plains into traditional Coahuiltecan territory created intense competition for resources, forcing the Coahuiltecans to confront unfamiliar warring groups. Additionally, southern movements of Chichimecah bands, driven north into Yanawana by conflicts and the spread of Spanish influence farther south, added to the pressure. These Chichimecah bands brought their own territorial claims and survival strategies, often competing with Coahuiltecans in their path.

Simultaneously, Spanish expansion disrupted the delicate balance of Coahuiltecans’ seasonal migratory patterns, which had been integral to their sustenance for generations. This disruption not only claimed land but also introduced European livestock and agricultural practices (the introduction of non-native plants) that further strained native foodways by competing with local flora and fauna. Disease, also introduced by Europeans via their symbiotic relationship with livestock, decimated populations and weakened social structures across Turtle Island.

FIRST SETTLERS

One of the earliest encounters with settlers that Yanawana experienced was at the end of an expedition led by Friars Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares and Isidro Félix de Espinosa in 1709. Olivares and Espinosa were escorted by Captain Aguirre and 14 soldiers, having left from the Rio Grande toward the Texas Colorado River. The expedition was an unsuccessful attempt to reconnect with east Texas natives, after the closure of east Texas missions years prior. Upon coming across, what is now called San Antonio, Olivares and Espinosa would write that they were, “impressed with the land and availability of water”. This expedition and the Friar’s impression of the land greatly influenced the later settling of the area.

By 1716, Spain ordered the re-establishment of east Texas missions in response to the growing threat of French outposts in the area. Friar Espinosa accompanied this new charter to east Texas, and the force would pass through ‘San Antonio’ again. Returning to Yanawana, Espinosa highly praised the area for its clean clear waters and abundance of fish and food. Espinosa’s praise of Yanawana would later influence Governor Martín de Alarcón to embark on an entrada to ‘San Antonio’ by 1718.

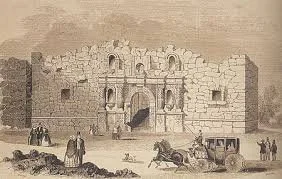

The Empire of Spain allowed Alarcón his entrada and the establishment of a mission and presidio in Yanawana. The settlement of ‘San Antonio’ was to act as an intermediate point between the Rio Grande front and east Texas missions, further establishing Spain’s rule over the lands. Friar Olivares accompanied Alarcón in 1718 and headed the establishment of the San Antonio missions and presidio.

Common verbiage around the missions regurgitates how they created a ‘safe-haven’ by providing food, shelter, protection, and resources for natives of the region. This narrative speaks as if the people of the land were eager to release their own beliefs, customs, culture, teachings, and lifeways to become indoctrinated into the settler’s faith and views. This is a skewed and romanticized perspective led by the colonizers. In reality, by the time the missions began appearing, Coahuiltecans had already long endured many phases and effects of colonization pressuring from all directions.

FRAGMENTING LIFEWAYS

The lattice of colonization unraveled the Coahuiltecans' delicate entanglements with the land, fracturing their intricate ecologies and lifeways. They were more than mere inhabitants; they were co-creators of a symbiotic dance with the land’s seasonal rhythms and beings. Each plant, river, and hill was a node in an intimate network of survival and meaning—a reflection of their collective spirit inscribed on the landscape. The arrival of Spanish settlers did not merely impose foreign rule; it destabilized these lifeways, by way of invasive vectors: livestock, alien flora, and the rigid geometries of agriculture that unsettled the native matrices.

Alarcón’s company included nearly 100 people and a host of non-native livestock ranging from cattle to sheep to chickens to mules and horses. While these animals grazed, native grasslands were fragmented and the soil’s resilient scripts were eroded leading to the spread of invasive European plants. This disrupted the ecosystems that the Coahuiltecan depended on for food, medicine, shelter and so much more. Livestock frightened off or competed with our wild animals, thinning and reducing game animal populations. This forced Coahuiltecans to rely on livestock for sustenance. Additionally, livestock trampled or consumed many of the native plants Coahuiltecans harvested, forcing them to alter their traditional food-gathering practices. Livestock required significant water resources. Rivers and springs—once lifelines of cultural and spiritual sustenance—were commandeered, diverted into the settler grid for livestock and fields, leaving the native water commons desiccated and contested. This encroachment restricted the Coahuiltecan’s access to clean water, crucial for drinking, cooking, and religious practices. In this semi-arid theater of conflict, fences emerged as symbols of control and demarcation, severing the Coahuiltecans' access to the interconnected spaces they once navigated with fluid sovereignty. Just as the Spanish expeditions disrupted large game migrations essential to the Coahuiltecans’ nomadic lifestyle, they also displaced tribes. These converging forces left many native groups, specifically Coahuiltecans, with little choice but to seek refuge within the missions. Not out of a desire for religious or cultural assimilation, but as a desperate response to the overwhelming disruptions they faced This was not assimilation by choice but a survival calculus within an imposed architecture of power—a lattice now twisted and deformed, their autonomy sacrificed to the machinery of conquest.

Military might of Mexican, Texian, and American origin, stand to uphold each Nation’s borders and lines of demarcation of territorial control. This defense of a country’s ‘territory’ has resulted in the various wars that influenced the creation of borders. The U.S.-Mexico Border was shaped by colonial infighting and native pilfering. Long before the nation-states arose with its maps and fences, the lands that stretch from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean were home to tribes like the Payaya, Tohono O'odham, the Apache, the Comanche, the Tigua, the Kumeyaay, and many others who moved freely across what would become the borderlands.

These people are the original witnesses, their stories marked in the earth, not by conquest but by the endurance of their sovereign presence.